'Faster, Better, Cheaper' – how a management strap-line contributed to the Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster

A Cultural Analysis of the NASA Space Shuttle Programme

The Space Shuttle Columbia was lost during its re-entry into Earth's atmosphere on February 1, 2003. The orbiter disintegrated over Texas and Louisiana as it descended toward a landing at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The investigation determined that the loss of Columbia was due to damage sustained to the shuttle's thermal protection system during its launch. A piece of foam insulation from the shuttle's external tank struck the left wing during liftoff, creating a hole that allowed superheated gases to penetrate the orbiter during re-entry.

All seven crew members tragically lost their lives in the Columbia disaster. The crew consisted of Rick D. Husband, William C. McCool, Michael P. Anderson, Kalpana Chawla, David M. Brown, Laurel B. Clark, and Ilan Ramon, the first Israeli astronaut.

The Columbia disaster led to a suspension of the Space Shuttle programme, a reevaluation of NASA's safety procedures, and changes to the shuttle's design and operational protocols. The tragedy had a profound impact on the space agency and the space exploration community as a whole.

Cultural Analysis

This analysis of the NASA Shuttle Programme culture focuses upon the leadership and management culture which contributed to the tragic loss of the seven crew members.

Central to this dialogue are the organisational, rather than the mechanical failures, especially the concern that engineers had expressed about debris impact, and the failure of management to actively engage with these concerns.

This is most publicly evident in this short extract from the news conference held on the 5th February 2003, four days after the Columbia Space Shuttle had disintegrated during re-entry:

“Right now, it just doesn't make sense to us that a piece of foam debris could be the root cause of the loss of Columbia and its crew. It's got to be another reason."

Ron Dittemore, Shuttle Programme Manager

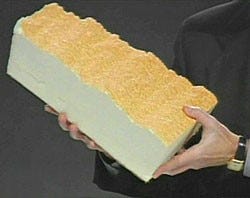

As Dittemore held the foam sample up in front of journalists he went on:

"It's fragile, it's easy to break and it's easy to break up into particles. It's very lightweight. ... I don't think there is an embedded ice question here, I don't think this came off as a chunk of foam and solidified with ice. When it hits the wing, this piece of foam disintegrates. Although we're going to look, we did not have icing conditions that day. We didn't have the ice, it's impervious to water. So it's something else. It's something else."

Unfortunately for Dittemore, it didn’t prove to be something else. What’s more the management team had been repeatedly warned and informed by engineers that not only was this an accident waiting to happen, but that they had observed the strike on the wing by foam debris, that their computer simulations had predicted that the consequential damage to heat protecting tiles would have exposed the wing to intolerable heat on reentry which would have rendered the shuttle impossible to fly. All of which were confirmed by the subsequent Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), August 2003.

MANAGEMENT

Space Shuttle Columbia (OV-102) flew 28 missions, gathering 300.74 days spent in space with 4,808 orbits and a total distance of 125,204,911.5 miles (201,497,773.1 km) until its final mission STS-107.

STS-107 was the 113th flight of the fleet and the 88th since the Challenger Shuttle had exploded after launch on the 28th of January 1986 due to a problem with seals in a joint in the shuttle's right solid rocket booster.

In the course of these 17 years between Challenger and Columbia the management culture of Shuttle Programme had changed considerably.

In 1992, Dan Goldin, the NASA Administrator (head of NASA), advocated that NASA adopt the ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’ (FBC) philosophy. The idea was to reduce the cost of each space mission significantly by taking more risk. This would enable far more missions to be flown. Each would be less ambitious, but the net return would be more science for the same total cost.

Over the next 11 years that focus came to predominate management thinking in NASA.

CAIB described this as follows:

“Little by little NASA was accepting more risk in order to stay on schedule”

Budgets were lowered by 21% between 1991 and 1994 and the NASA workforce by 25% with many technical areas described being ‘one-man-deep’.

The consequence of ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’ was to move away from ‘safety first’, to what was described as a ‘go-fever’, which was tendency to be committed to a course of action due to ‘sunk costs’, i.e. expenditure which had already been spent on the project and which would have been deemed to have been lost if the schedule was not maintained.

LEADERSHIP

If Leadership is the capacity to make decisions and to influence others, then it would seem to have been considerably affected by the Management focus upon ‘Faster, Better Cheaper’.

This is best represented in the difference between the probability of failure of the Shuttle between engineers and managers, where engineers reckoned a probability of failure was 1 in 100, while managers believed it to be 1 in 100,000. Richard P. Feynman, 1986 Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident.

His commentary of the impact of such a disparity of opinion on behaviour was captured as follows:

At the bottom you have the engineers yelling "Red Alert! This is a serious problem!".

Their managers report up the chain "We have a problem."

The middle managers report up the chain "We may have a problem."

The senior managers report up the chain "There are some issues."

And the directors hear "We may have an issue." The message at the top is radically different from the view at the bottom.

In part, this difference was due to the failure of leadership to create a common sense of purpose, vision and guiding principles which would then inform the behaviour of everyone in the organisation.

Unfortunately, managers were overly influenced by a reliance upon past success. Even with memories of the Challenger disaster, the more flights of the Shuttle which were successfully completed the more diminished became the perception of risk by managers.

Such a subjective view of risk was fed into the managers’ confirmation bias, with every passing flight being taken as confirmation of the managers’ knowledge, judgement and expertise – even in the face of disagreement from engineers.

“The organizational causes of this accident are rooted in the Space Shuttle Program’s history and culture, including the original compromises that were required to gain approval for the Shuttle, subsequent years of resource constraints, fluctuating priorities, schedule pressures, mischaracterization of the Shuttle as operational rather than developmental, and lack of an agreed national vision for human space flight. Cultural traits and organizational practices detrimental to safety were allowed to develop ...” CAIB

Over the years of successful flights, the focus upon Safety became less and less. This is best captured by term ‘organizational drift’:

Organisational Drift is the gradual, and apparently imperceptible, degradation of standards that leads to a failure to address shortcomings that are having an adverse impact on performance. Institution of Chemical Engineers

In other words, Organisational drift is the slow erosion of correct process and procedure; it is the gap between what processes say should happen, and what actually occurs or can be described as ‘work as imagined’ vs ‘work as done’.

Compounding this phenomenon was the impact of cognitive dissonance, which became even more apparent after the disaster had occurred.

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological conflict which occurs when a person is required to hold two conflicting beliefs. In the case of Ron Dittemore and the NASA Space Shuttle Managers, the idea that debris damage, which they had discounted as a safety risk, could actually have been the cause of the tragedy was completely dissonant with their own belief in their competence and capacity.

Was it any wonder then that Dittemore discounted the Foam Debris risk so publicly just four days after the disaster? For him to have accepted that cause would have been to place a question mark over his own, and his close colleagues’, professional judgement.

WARMTH

Warmth relates to the organisation’s tendency towards caring, concern and nurturing of people.

From this perspective it’s difficult to make judgements about the true extent to which the NASA Shuttle Programme exuded a sense of Warmth, but there are a few indicators available which might suggest that it was in deficit.

Firstly, and this term did not exist in 2003, the extent to which the organisation created a sense of ‘psychological safety’ for people to speak up and offer candid opinions.

The findings of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board repeatedly mention the hierarchical nature of the organisation facilitated against open communication. This undoubtedly led to problem with sharing opinion and the willingness of engineers to openly challenge managers.

The pressure to do things ‘Faster, Better, Cheaper’ also seems to have contributed towards a focus on delivery over safety, with this being reinforced by the gradual ‘organisational drift’ which took place over the seventeen years between the Challenger and the Columbia accidents.

This focus also seems to have impacted upon some of the decisions taken by management following reports of a foam debris strike on the wing on take off.

Engineers repeatedly requested that the Management approach the US Air Force to seek their help in capturing high-quality images of the wing to ascertain the extent of any damage.

Management never followed upon these requests mainly due to the mission days which would be lost by having to change course to enable images to be taken.

There’s also another possible reason which relates to cost and dilemma which Management might have faced were damage to have been proven by the images.

It relates to ‘what-if’ scenarios and the possible financial implications of the actions that would have to be taken in such circumstances.

The ‘What-ifs’ run as follows:

The damage is proven to have occurred

The wing might or might not be damaged sufficiently to impact a safe landing

A judgement would have to be made one way or the other

Damage from foam debris was seen on 79 of 113 Shuttle flights from 1981 to 2003 and yet Shuttles continued to arrive home safely.

To launch a rescue Shuttle would cost in the region of $450,000,000

To allow the empty Columbia to crash into the pacific would be a $2 billion loss

This is speculation but would a manager in such circumstances and operating in such a culture really want to be placed into such a dilemma? Might it not be easier to rely on the successful track record, despite foam debris hits, and not ask for the additional images to be taken?

As it was the Shuttle had sufficient oxygen for another 30 days and a second Shuttle could have been sent up with a minimal crew to rendezvous with them and bring them home. Such a plan was only outlined by the CAIB and was not part of any Shuttle Programme contingency plan at that time

EDGE

Edge, or focus on performance. results, and success were very strong features of the Shuttle Programme culture, and to a great extent overtook many other aspects of the organisation’s culture.

The scientific mission took precedence over safety.

Delivery of the programme was the key driver.

The schedule took on more importance than safety.

The repeated success of flights since Challenger in 1986 simply fed that focus and over-confidence of managers that they could overcome any technical problems that came their way.

In many ways such an Edge created what the CAIB called a ‘cultural fence’ between managers and engineers, which only served to reinforce blindspots:

“In fact their management techniques unknowingly imposed barriers that kept at bay both engineering concerns and assenting views and ultimately helped to create ‘blindspots’ that prevented them from seeing the danger the foam strikes posed.” (CAIB p170)

LEARNING

Rather than learning, the principle theme emerging from the Columbia Space Shuttle accident is what might be termed ‘unlearning’.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board concluded that NASA was not a learning organization. Even after numerous instances of foam loss and a very serious debris strike just two flights before the launch of the Columbia, foam losses were still not considered dangerous enough to halt flights. In similar fashion, prior to the Challenger accident, instances of eroded seals between the segments of the solid rocket boosters were recognized but tolerated. The CAIB saw this pattern as evidence of “the lack of institutional memory in the Space Shuttle Program that supports the Board’s claim … that NASA is not functioning as a learning organization” (CAIB, 127).

Professor Julianne G Mahler, described how that the period between the Challenger disaster in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 was a period of ‘Unlearning’. She described how during that period there had been lots of reorganisation, restructuring and downsizing within the Shuttle Programme. With each of these events there was a loss of organisational memory which not only had a very negative impact upon the organisation’s ability to continually learn and progress, but actually operated in the reverse direction leaving it very exposed to the event which eventually took place on the 1st February 2003.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

The fact that in 2003 the Shuttle Programme was still running on 1970’s technology didn’t really provide the space for innovation that we might be currently witnessing in the Space X programme.

There was little evidence of creativity and innovation within the launch programme, whist recognising that the science taking place during the missions wold likely have been very cutting edge.

The fact that no imagination or effort was put into considering how to make the astronauts even safer, or to have an innovative contingency plan in place should something go wrong seems to reinforce the perception that the organisation was singularly focused upon delivering the schedule above everything else.

TEAMWORK

Teamwork appears to have been horizontal rather than vertical within the NASA Space Shuttle Programme. On reading the Accident Investigation Board the notion of hierarchy and levels of authority seems to have be rigorously imposed.

There is no strong indication of Teamwork, which runs very much counter to the original NASA culture which resulted in the moon landings of the Apollo Programme.

There is no equivalent to the apocryphal story of President John F. Kennedy visiting NASA for the first time in 1962. During his tour of the facility, he met a janitor who was carrying a broom down the hallway. The President then casually asked the janitor what he did for NASA, and the janitor replied, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

By 2003 that sense of unity did not seem to be as apparent.

CONCLUSION

Throughout my analysis I was convinced by the genuine desire of everyone involved in the Space Shuttle Programme to look after the astronauts in their care, and to do the best job they could possibly do.

However, for a variety of complex reasons the culture of the organisation was compromised by the demands to deliver ‘Faster, Better Cheaper’.

This led to an ‘organisational drift’, a ‘cultural fence’, and a state of ‘unlearning’ all of which contributed to the disaster that led to death of seven people.

Yet my abiding reflection is that the NASA Space Shuttle is no different from many organisations I’ve worked in, or worked with. It’s just that the high stakes nature of the consequence of such behaviour is much more apparent when a Shuttle falls out of the sky, compared to the school, the manufacturing business, the bank, or the hospital where such cultures and leadership continue to exist.

Notes:

Each Leadership Unlocked Newsletter uses elements of the Ceannas Ecosystem to analyse organisations or individual leaders. The Ceannas Ecosystem is made up of three analytical frameworks, composed of the seven Leadership lenses; the seven building blocks of the Cultural Footprint; and the seven components of the Wheel of Wise Leadership. In our work with leaders we help them to embed these frameworks to the extent that they inform their thinking, leadership behaviour and decision-making to do “the ‘right’ thing, at the ‘right’ time, for the ‘right’ reasons”. Contact us on info@ceannas,com to find out more about our philosophy, methodology, programmes, workshops and technology.